Kokan Shiren On Contemplating Empty Dharmas While Dying

Kokan offers a step-by-step process to awaken during the dying process and a 'if that doesn't work, try this' for 'ignorant persons of lesser capacity.' This last point is in contrast to both Dahui and Dogen.

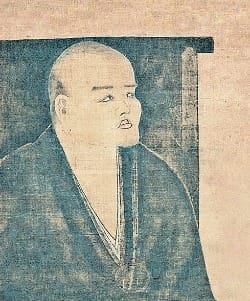

Kokan Shiren 虎関師錬 (1278–1346) was one of the extraordinary masters of what Steven Heine calls a remarkable century of transmission and transformation. In this post, I'll focus on his dying and death instructions, because Kokan offers a step-by-step process to awaken during the dying process and a "if that doesn't work, try this" for "ignorant persons of lesser capacity." This last point is in contrast to both Dahui and Dogen (see earlier posts).

Again, my primary purpose for this death series is to provide you with information for your own dying and death process, including a range of resources for how to practice at this crucial time. I don't mean to imply that you are among those of lesser capacity, but if you see yourself that way, well, you are in good company.

Jakusan, may great good fortune adorn your path of awakening!

First, a bit about Kokan

Although Kokan is not well-known today, he was a famous Zen master in his day, even receiving the title of "National Teacher" by the emperor.

As a child, Kokan first became a Tendai monk, but after a year, left Mt. Hiei to train with Rinzai Zen Master Tozan Tansho (1231-1291; successor of Enni who had the unfortunate death mentioned in How To Practice During the Long, Last Moment) of Tōfukuji. Unfortunately, in 1291, Tansho was stabbed to death by a thief, so Kokan went on pilgrimage, eventually training under another of Enni's successors, Kian Soen (1261-1313) of Nanzenji.

Kokan also trained with the Chinese émigré master, Yishan Yining (1247-1317; Japanese, Issan Ichinei), the first teacher of Muso Soseki, also discussed in a previous post:

Muso, you might recall, found Yishan to be an unyielding master whose teaching was impenetrable. Yishan told Muso, for example, “There are no expedient means, nor is there any compassion."

However, Kokan saw quite a different side of Yishan:

When Yishan asked Kokan for the collected biographies of great masters in Japan in order to familiarize himself with his adopted country, Kokan could not deliver – no collected biographies existed at the time. Kokan was profoundly embarrassed that no one in Japan had done this work, and so he set about to create such a text. This resulted in what is regarded as his master work.

Steven Heine writes:

Kokan also wrote an important commentary on The Lankavatara Sutra, titled The Heart of the Words of All the Buddhas, a popular dictionary for rhyming Chinese phrases, and was a well-regarded poet. As for our present topic, dying and death, Kokan wrote A Treatise on the Meaning of Illness (Byōgiron), a text that has yet to be translated. According the Jacqueline I. Stone, this text is "the only early medieval Japanese work to set forth detailed instructions for deathbed practice in a Zen mode."

In what follows, I rely on Stone's summary of Kokan's text.

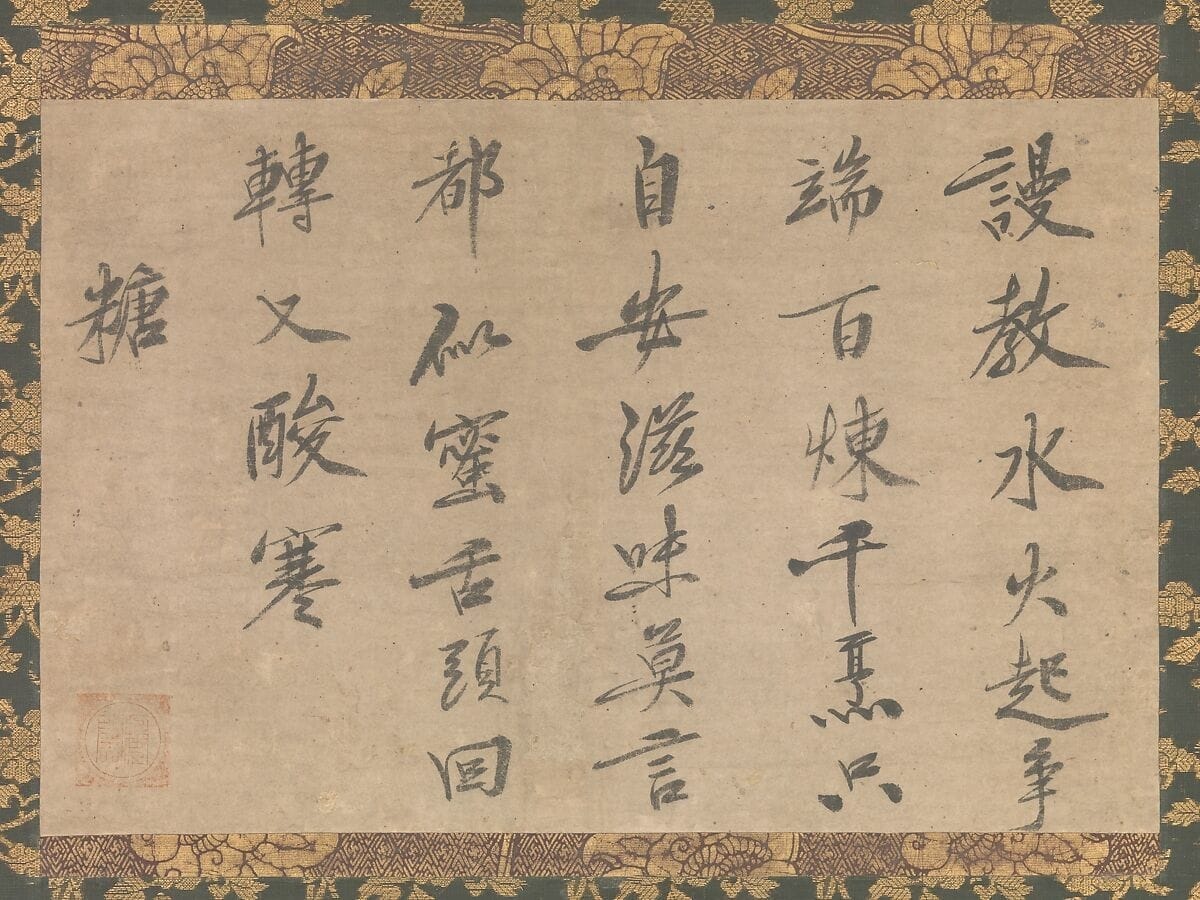

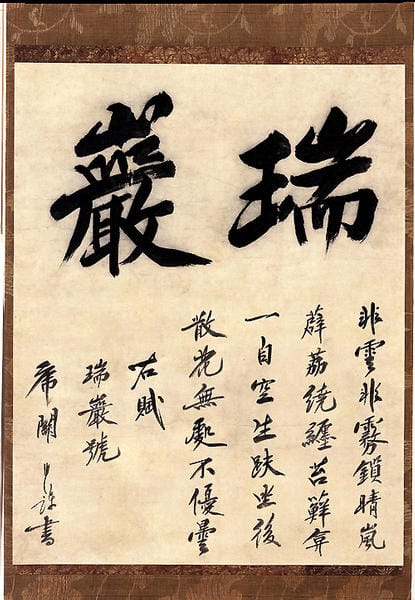

Finally, Kokan was an outstanding calligrapher. See the piece at the top of this post and what follows below, a verse of praise to one of his successors, Zuigan Dongen:

Transforming unwholesome karma at the time of death

Kokan's A Treatise on the Meaning of Illness, includes a section on indicators of a person's karmic conditions while they are living that foreshadow their post-mortem destination. Stone notes that these include, "[...] ominous dreams—for example, of a dead person shouldering another dead person; of having to cross a path crawling with toads; of walking among graves; or of entering a dark house and being unable to get out."

As death approaches, such inauspicious visions may continue, and include "[...] evil spirits arranged in the air, fierce beasts closing in on one’s bed, being threatened by a hot iron staff, or a fiery cart arriving to meet one."

Fortunately, Kokan also offers a practice to meet such apparitions and transform our karma and post-mortem destination – a three-step "contemplative discernment of the empty nature of karmic action." Even practitioners with enormous shitloads of unwholesome karma can, by the power of the eye of insight, receive protection from the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, transform their karma – and their post-mortem destination.

Not everyone, of course, has such intense dream-like apparitions, although I have met some practitioners who report undergoing such experiences every night. But everyone has delusions, aka, sense experiences and distorted formations. Therefore, even if you are among the fortunate who don't have such ominous dreams, you don't need to wait for horrendous pre-death apparitions to undertake this practice. Indeed, the easy way is to do the difficult (and subtle) work now.

The first step

Whether you take up the work now or wait until you are dying, it is notable that most instructions for dying and death include the encouragement in our last moments not to freak out, but to be steady in our awareness. Kokan joins the chorus of other masters on this point. Not giving way to fear (that's different than not feeling afraid), however, is the precondition for the first step, not the first step itself.

I think here of the Vine student, Dieter Gensho, who died last year. In his last text to another Viner, he said, "I'm very afraid and very excited to see what comes next."

Kokan then continues, encouraging dying people who experience troubling apparitions, to examine:

Troubling apparitions are just the mind, so the instruction is to turn the light around to see emptiness, see nature as it appears as a troubling apparition. If you dwell in this awareness in this nen, then you will in one nen, "[...] perfect the contemplation of all things as empty and immediately transform the terrifying visions into auspicious ones."

Seeing emptiness, seeing nature is a qualitatively different experience than observing phenomena as impermanent or observing phenomena as emptiness. Seeing emptiness, seeing nature isn't a thought with a subject who thinks, "Oh, this apparition is impermanent," or "Oh, this apparition is empty." Such thoughts don't have the power of seeing emptiness, seeing nature.

When seeing emptiness, seeing nature, the arising phenomena is the self. This is what Kokan calls "perfecting the contemplation." However, it isn't necessarily one and done, but may well be an ongoing process that will require repeated turning the light around as the myriad phenomena arise.

Kokan notes with confidence and optimism that at some point the troubling apparitions will transform into auspicious signs. Such auspicious signs include the arising of visions of our happy places and people, such as "[...] pleasure groves and palaces (indicating rebirth in the heavens) or of beloved and familiar people, such as parents and siblings (indicating rebirth in the human world)."

The second step

But apparitions of your happy place and people are still apparitions. So Kokan's second step is to remain steadfast in seeing emptiness, seeing nature through these karmically arising, mind-produced apparitions as well. If one remains steadfast in awareness of the empty auspicious signs, then “superior signs" will arise.

Superior signs include:

A regular reader of these posts might recognize the above signs for birth in a Pure Land from Why is the Long, Last Moment So Important? as one of the best post-mortem outcomes (aka, outcome #4). But Kokan presses the practitioner not to settle for a Pure Land.

The third step

Kokan's instructions encourage us to continue to turn our contemplation, seeing emptiness, seeing nature into these superior signs as well. In this, he cites Zen master Qianguang Huansheng (906–972):

After realizing the emptiness of superior signs, the practitioner then abides quiescent in no mind and greatly awakens to the birthlessness of all dharmas, fully entering the Bodhisattva path with no backsliding.

Stone summarizes Kokan's process here:

But what if you are not a person of great capacity, or one with the superior power of practice in the final moments?

Single-mindedly recite Namu Amida Butsu

Kokan acknowledges that not everyone is a person of great capacity. For those "ignorant persons of lesser capacity," Kokan recommends the nenbutsu practice of Namu Amida Butsu. He offers this, though, in a manner informed by Zen training:

In other words, just completely become one with Namu Amida Butsu, without mixing it with any other thoughts, just as Dogen instructed for Namu kie Butsu.

Stone summarizes Kokan's instructions for dying here:

Kokan's teaching for dying and death, like the other masters we've examined (Dahui and Dogen), embraces the basic elements of the general Buddhist perspective on dying and death. Those elements include a post-mortem destination, the notion that practice before dying and death contribute to a more positive post-mortem destination, and that there is a potent possiblity for practice in the long, last moment. Kokan uses a reflection on emptiness that is widely adopted across dharma traditions to effect a positive post-mortem outcome. He also offers another practice if the emptiness meditation isn't going so well – just become Namu Amida Butsu.

Many more posts coming soon

Then we'll have time off from writing before, during, and after the 7-day sesshin that begins Sept 26.

Coming this week

Zen: One School, One Mind Workshop, Part 3 (for paid subscribers)

Coming next week

"How Can I Liberate Beings Such as These?" The Lotus Sutra and Dogen on Buddha's Zazen (for all subscribers)

Coming next in death

Hakuin Zenji's "Now You're Dead: Where Did the Main Character in Your Drama Go?"

Coming soon at Shake Out Your Sleeves and Go

"No Quarter for Escape: an Interview with Shodhin Geiman Sensei."

Geiman Sensei is the teacher at the Chicago Zen Center and author of Alone in a World of Wounds: A Dharmic Response to the Ills of Sentient Beings (all Shake Out Your Sleeves And Go posts and podcasts are currently open to all readers).