404 Adverse Meditation Experiences

"If one is able to skillfully apply the mind, then the four hundred and four kinds of disorders will naturally be cured." - Zhiyi

First, a caution:

If you take up meditation practice with intensity, you will experience Adverse Meditation Experiences (AME). These will arise most often within meditation itself and could include anxiety, hostility, visions, and intense passion, including of the sexual variety. Outside of sitting meditation, occasional insomnia is also reported by some practitioners.

However, some practitioners also report sleeping soundly. Then, there are other practitioners who report an unusual sense of stability and clarity in daily life (even in difficult situations), as well as upwellings of bliss, and outbursts of truth-telling, sometimes in socially inappropriate situations.

In addition to the above, there are other effects as well. These include back aches, especially of the neck, shoulders, and low back. Many practitioners report knee, hip, and ankle pain, and there is also an increased likelihood of developing sciatica. These physical ailments are especially associated with, but not limited to, those who do not properly align their zazen pose.

Although extreme mental health crises are rare, if you have had such an experience, or have a pre-existing psychological condition that might predispose you to such outcomes, it's important that you consult with a psychologist prior to engaging in intensive practice. Then, find a meditation teacher who can work with your particular circumstances. It is generally advised, and I strongly agree, that it is unwise to undertake intense meditation practice without a teacher. See this for more:

If you have AME that are more than mild and occasional, consult with your teacher and consider working with a psycho or physical therapist.

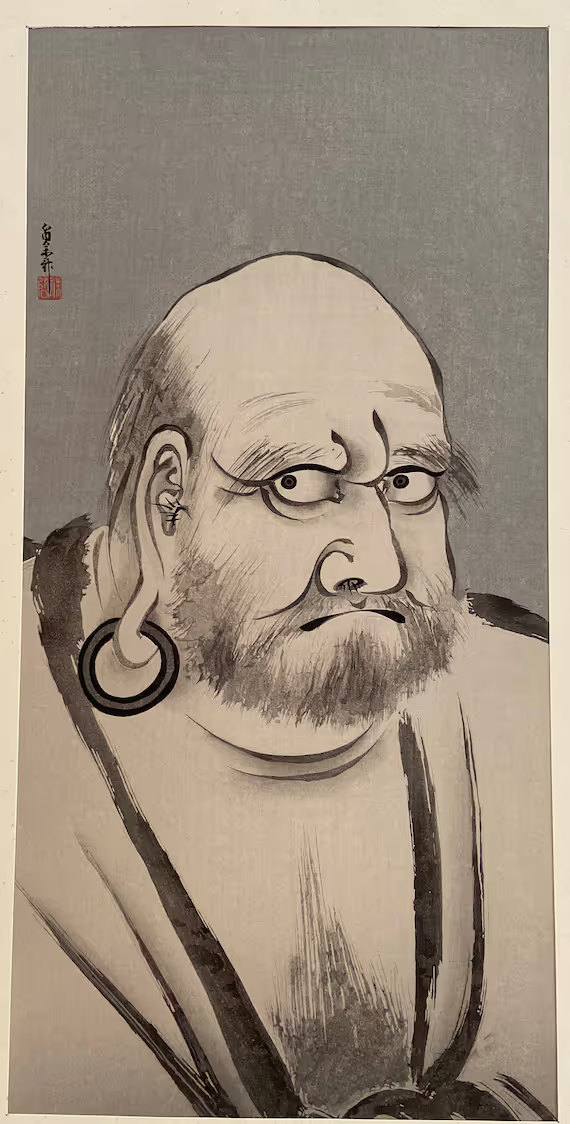

All that said, the Buddhist tradition itself offers a rich variety of resources to support us as we traverse through the difficult terrain of the body-mind. Buddhist teachers should be well-versed in at least some of this this traditional literature. One of my favorite sources is the old master Zhiyi (538-597) who said,

Notable, isn't it, that Zhiyi identifies 404 disorders? That's a lot! I barely scratched the surface in my disclaimer above. A couple years ago, I wrote a piece addressing this contemporary issue, "Adverse Effects of Meditation." Among other things, I wrote:

In short, if you want a joy beyond all normal joys and profound insight into the subtle nature of reality, it isn't going to be sledding downhill all the way. But if your practice is limited to ten to fifteen minutes of meditation a day, it is unlikely that the meditation will be the direct cause of any of the above adverse effects. If you are sitting with diligence for a couple hours a day and participating in retreats as much as you can, then you are very likely to experience some of the above.

If you'd like to read the whole piece, you can find it here:

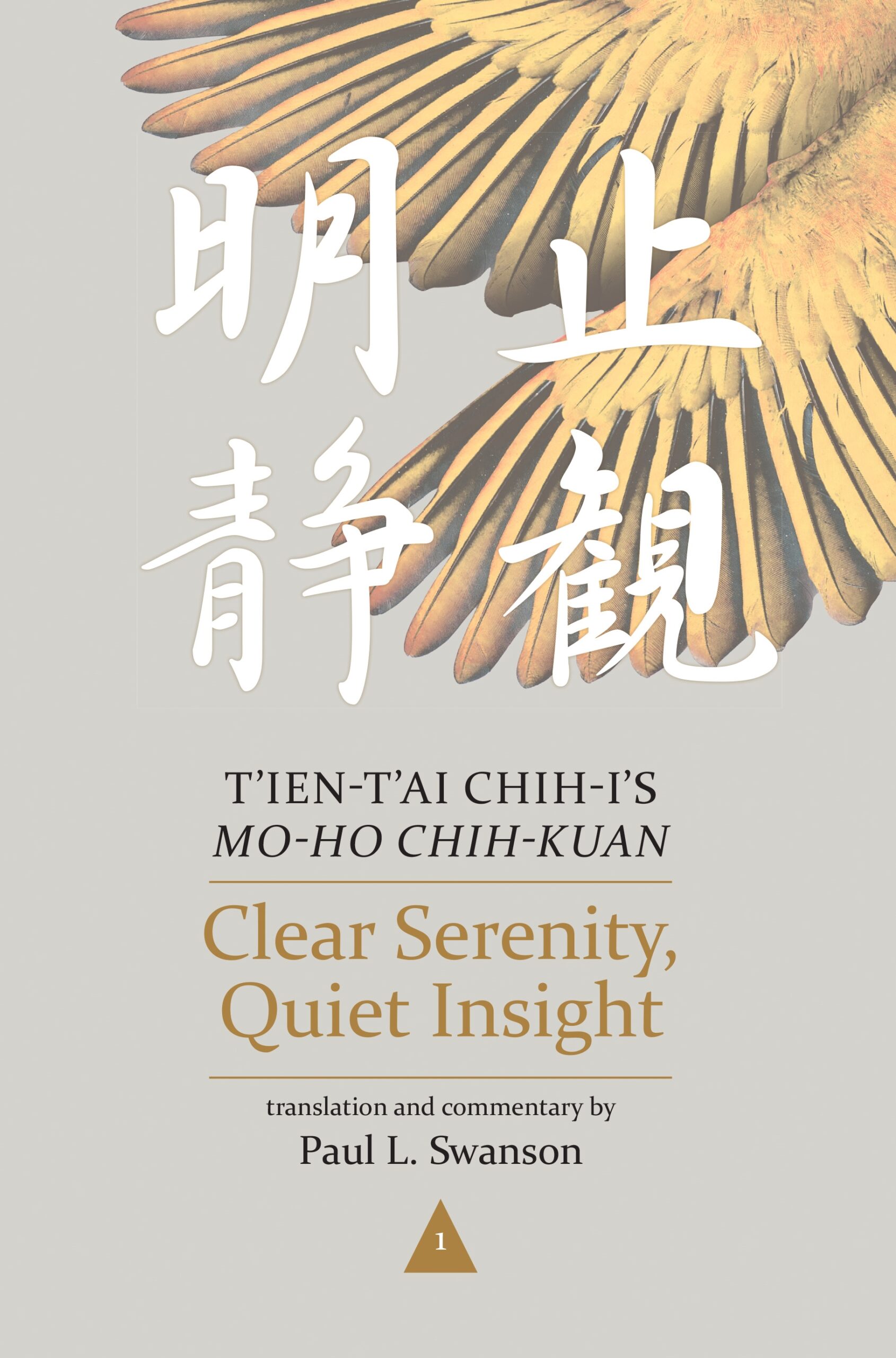

In the rest of this post, I return to the topic and will go into more detail on the teaching of Zhiyi regarding AME, still only just touching the tip of the iceberg of Zhiyi's voluminous offerings on this subject. My intention is to get to the heart of both the attitude and method that Zhiyi advised for working with AME. The source material for this post is The Great Stopping and Seeing (Mohe Zhiguan, 摩訶止觀, published as Clear Serenity, Quiet Insight, trans. Paul L. Swanson), 747-750. The entire 850 pages of the second volume address this topic both directly and indirectly.

There are those who say that AME aren't addressed in Buddhism. This is clearly not the case. In what follows, I'll focus just on a few passages, sharing Zhiyi's teaching and providing a few thoughts to highlight the most important points.

Note: I have modified the translation in order to align it with the Vine vernacular.

Working through afflictions

Zhiyi begins:

If you are diligent in both practice and understanding, then the three obstacles and the four Maras will confusedly contend with each other and arise; this will multiply your darkness and magnify your distractions, thus shading and disturbing the light of your concentration.

Zhiyi starts off with quite a powerful statement: "If you are diligent in both practice and understanding" then you will, in other words, experience AME. They are not a bug, but a feature of diligent meditation practice. When adverse experiences arise, many of us tend to wonder if we are defective, or blame them on the practice. Zhiyi encourages us to see these experiences as good signs that we have what we need to awaken (i.e., abundant delusions) and an opportunity to "skillfully apply the mind" (i.e., the method).

What are the specific obstacles Zhiyi referred to? "The three obstacles" are: 1. the veil of delusion resulting from past actions; 2. afflictive hindrances (i.e., the whole great field of greed, anger, and ignorance); and 3. karmic hindrances that obstruct accurate seeing and appropriate behavior.

As for the four Maras, "Mara" is literally "The Destroyer," and in the buddhadharma is more of a trickster (think, coyote) than a devil like the Christian Satan. The four Maras are as follows: 1. the Mara of harmful desires that injure oneʼs body and mind; 2. the Mara of the five aggregates (skandhas) of form, feeling, perception, formations, and consciousness that cause beings suffering; 3. the Mara of death; and 4. the Mara that tries to prevent living beings from doing good.

To summarize, here are the above obstacles that arise when we are diligent in both practice and understanding: delusions, strong emotions, inaccurate perceptions, self-injurious desires, the aggregation of a self itself, our impending death, and our propensity to harm others. And Zhiyi says also that all these obstacles are contending with each other! Phew.

The three obstacles and four Maras, then, are not something outside ourselves. It is definitely a "we have met the enemy and they are us" situation. This radically normalizes adverse meditation experiences. It could be said that "the self" simply is a mix of contending adverse experiences.

What can a diligent practitioner do?

Zhiyi's first piece of advice is attitudinal. When difficulties arise, instead of pathologizing the self ("oh, gawd, am I a mess!") or denigrating the practice ("oh, gawd, Zen is a mess!"), welcome the situation ("oh, gawd, that I'm having difficulty in the practice is a sign that I might be practicing diligently and now have the chance to apply skillful means in the midst of difficulty - just what I want!").

If the mind itself is the obstacle (aka, "the opportunity for awakening") and you have a good attitude about working with yourself, how then can we specifically and "skillfully apply the mind?"

You should not follow after, nor be afraid of these phenomena. If you follow after them, they will lead you to the unwholesome destinies; if you fear them, they will hinder your cultivation of the correct dharma practice. You should utilize seeing to see the darkness, and thus brighten the darkness. You should utilize stopping to stop the distractions, and thus the distractions will be quiescent.

The good news is that because we are the problem, we can do something about it. Specifically, don't follow after the obstacles and don't fear them. Or as I'd put it, when you see that you are chasing after an adverse experience, see the obstacle, then stop. When you see that you are afraid of an obstacle, see it, then stop.

This is to take refuge in the Three Treasures.

It is important here that Zhiyi talks about seeing then stopping; that's reverse of the usual order of first calming the mind - stopping - then seeing deeply. In the case of obstacles, though, if we first stop, we might wipe away the obstacle before we get a good look at it and see that it is really the self. This is referred to these days as "spiritual bypassing."

Zhiyi didn't seem to have a value judgment about wiping an obstacle away, but saw it as unskillful for awakening. By stopping first we erase our opportunity for awakening through the obstacle.

In a similar manner, Tetsugan Sensei and I often advise students to "touch and release." After we've touched the obstacle, then we can release it without ignoring it's true nature. Zhiyi, though, frames the practice a bit differently. He advises us to "see then cease."

For more on stopping and seeing, stop and see the following:

It's important to note that in advanced practice the work is to bring stopping and seeing together in prajna-samadhi. I'll be returning to that soon in a future post about the teaching of the Sixth Ancestor (Zhiyi makes the same point elsewhere).

Zhiyi continues:

[...] Vajra-like seeing can split the array of passionate afflictions, and these hard and strong feet [of stopping] can take you beyond the field of samsara. Wisdom purifies practice, and practice brings forth the progress of wisdom - [together] they illuminate, moisten, guide, accomplish, and thus adorn each other with brightness, as the two hands of a single body wipe and clean each other.

Seeing like a bolt of lightning that splits apart afflictions! Strong feet steadily walking as the breath of stopping. And "the two hands of a single body wipe and clean each other."

So lovely!

It is not that you should merely clear away the obstacles and inwardly progress on your own path, but you should also be diligent in mastering the sutras and treatises, and reveal them to others who have not yet heard them. Heal yourself and heal others, and thus be endowed with [the good qualities of] benefiting both [yourself and others]. Who else can be considered a teacher of people and treasure of the nation?

In terms of adverse effects of meditation, we started with an attitude, covered a couple skillful means, and now we're back to an attitude: get over yourself already. "Heal yourself and heal others." After all, the practice of the Great Vehicle is powered by compassion and the vow to carry all beings across. Such attitudes are also skillful means.

Apparently, the phrase "a teacher of people and treasure of the nation," is quite well-known, thanks especially to Saicho (767-822), the founder the Tendai school in Japan. If you deeply master the methods of working with the afflictive obstructions, I hope you will become a great teacher, pointing to the path, and carry beings across. What a treasure you would then be for all the humans and non-humans!

Again, learn from the Buddha's compassion, which has no hint of stinginess, and be of service to others by expounding stopping-and-seeing. Open the gate and tilt the store [of the Dharma] to "cast out" the mani jewel. The jewel then radiates light, causes jewels to rain from the sky, illuminates the darkness, enriches the poor, brightens the night, and saves the destitute.

Here's the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism's gloss for mani-jewel:

That's one helluva jewel.

You can go a far distance by driving a vehicle with two wheels, and a bird can fly high by flapping both wings.

Zhiyi closes this passage with a couple more metaphors. Seeing and stopping are like the two wheels of a motorcycle going straight on the winding road of this life. Stopping and seeing are like the two wings of a bald eagle soaring through the sky on a windy day.

May you deeply and diligently practice and understand the buddhadharma; thoroughly undergo the 404 obstacles, awakening through them all; and share your brilliant vision with all the many beings.

This post is open to all subscribers. For those of you who are paid subscribers, I appreciate your support of this work, making it possible for me to devote time to writing practice.

The comment section is open as usual to paid subscribers.

Coming later this week for paid subscribers: "What is the Color of the Cool Breeze? Fayan's Substance and Name"