Soto Zen Women Wake Up: A Review of "In This Body, In This Lifetime"

Awakening Stories of Japanese Soto Zen Women

Kogen Czarnik Osho, translator, and Esho Sudan Osho, editor, have performed a great service to the buddhadharma with their intimate care for the teaching of one of the great Zen masters of the 20th century, Sozen Nagasawa Roshi. Indeed, they have reached back and pulled Sozen Roshi's teaching from the abyss of the many forgotten women dharma masters. Kogen Osho and Esho Osho bring Sozen Roshi to us as she was received by her woman students – both householders and monastics. In This Body, In this Lifetime: Awakening Stories of Japanese Soto Zen Women, these great women of the Way share their bodhi minds, travails, and powerful awakenings (aka, kensho).

Why share something so intimate as your kensho? Kogen Osho writes:

In Sozen Roshi's time, women were conditioned to believe that they couldn't awaken. In our time, women, among others, are conditioned to believe that awakening isn't important. Or, that they're already awake, simply by sitting down in meditation. Or, that all that the buddhadharma has to offer is a self-soothing narrative. Nonsense! Unfortunately, women tend to be so involved in family and work, carrying a disproportionate share of the physical and emotional labor in both, that even if the aspiration arises, it often seems that they have insufficient time and energy left to devote to awakening.

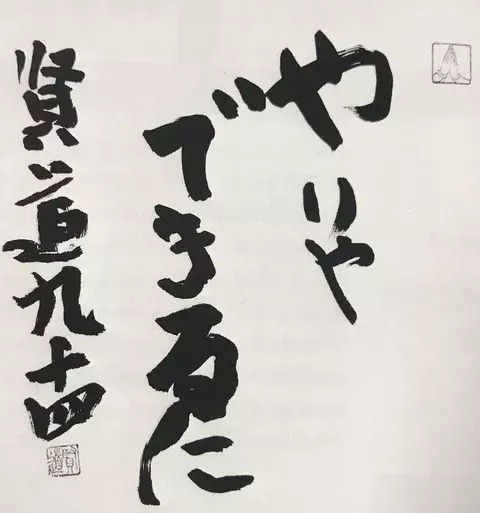

Kigai Oyamada, one of the women whose kensho story appears in In This Body, In this Lifetime, wrote after her kensho:

The "they" she speaks of here is us.

It's not, of course, about doing more, but about making awakening one's primary priority, letting go of other things (as in saving energy is gaining energy), and strongly advocating for one's practice in renegotiated relationships.

May the stories of these great women practitioners provide inspiration to go against the stream of conditioning and fully realize the bright world of awakening as soon as possible!

But talk about noise in the works! Many Soto Zen centers in the West, rather than clearly pointing to the way of awakening, add to the torrent of nonsense that floods spiritual cyberspace, confusing those who have aroused an initial aspiration to awaken. They spread the delusion that kensho isn't something Soto women should realize (because they're already awake) and, in any case, do not offer a training container in which the bright world of kensho is likely to manifest. Yet, these same centers (i.e., "rabidly anti-kensho," as a leader in one of these centers once wrote) intone Sozen Roshi's name, Kojun Sozen Daiosho, in what's known as the "matriarchal lineage."

They seem unaware of Sozen Roshi's very strong pro-kensho stance, and the rigorous do-or-die vigor of her training container. I imagine that Sozen Roshi might say, "Don't mouth my name while denying the vital importance of what I lived and died for!"

Given that an excerpt of the book, "Remembering My Child," is available now, and the book will come out June 17, 2025 (available for pre-order), in this review, I'll first introduce you to Sozen Roshi, offer you an excerpt about the importance of the post-awakening process from Sogen Saito Osho, and end with what is likely a controversial view on the importance of shame in the service of awakening, with an example from the text.

Sozen Nagasawa Roshi

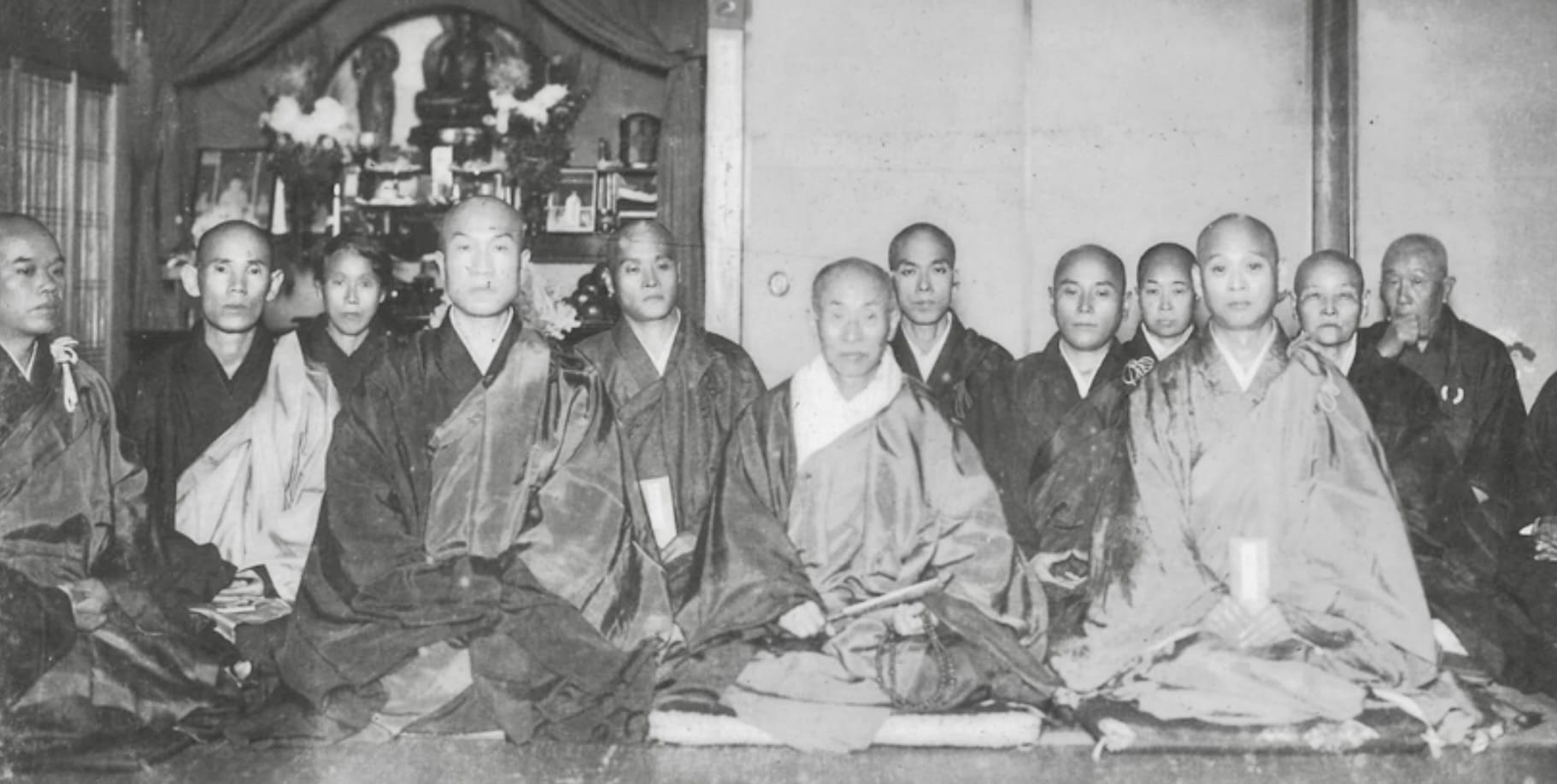

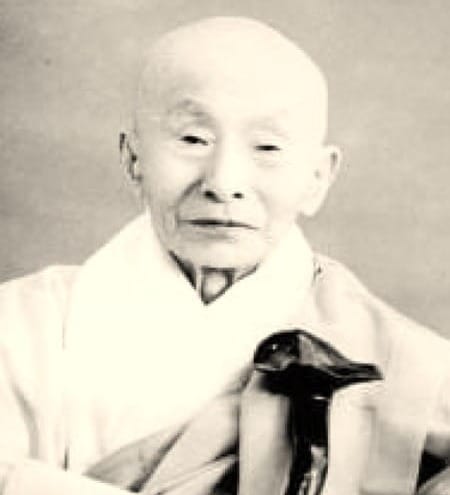

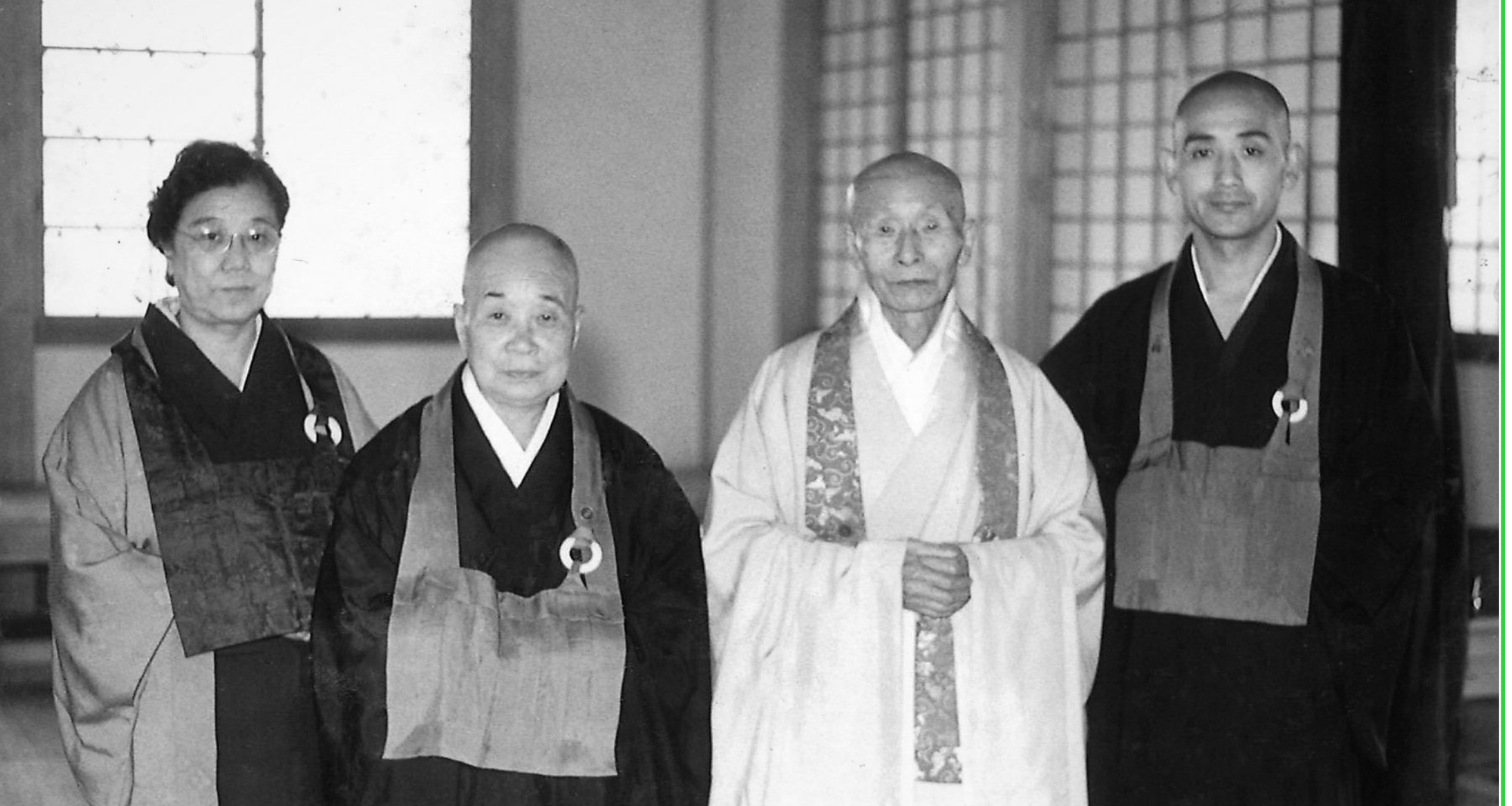

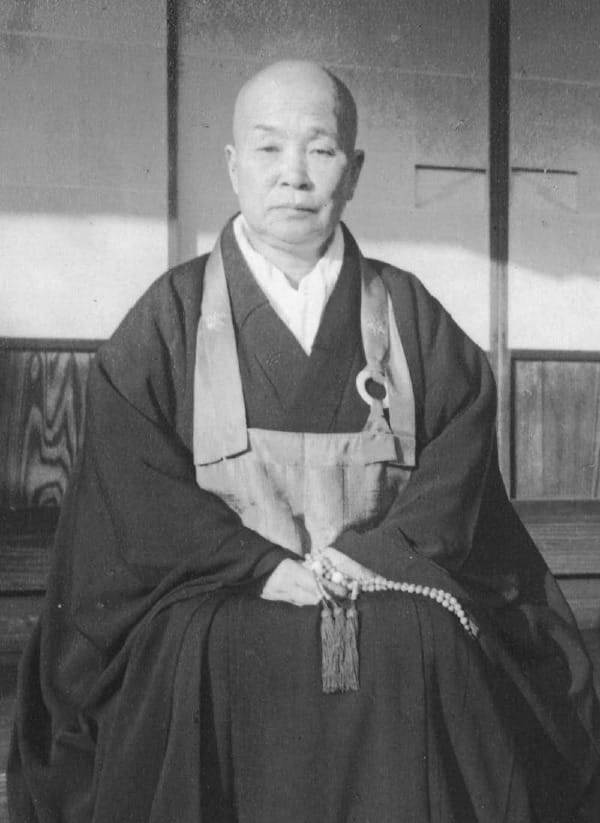

Sozen Roshi (1888–1971) was a successor of Daiun Sogaku Roshi (1871-1961).

Sozen Roshi became a homeleaver (aka, nun) under Sogaku Roshi while the latter was a professor at the Soto school's Komazawa University. With his support, Sozen Roshi was able to train at Sogen-ji, a Rinzai training monastery known as "the demon's dojo." When Sogaku Roshi became the abbot of the Soto training monastery, Hosshin-ji, she trained with him there. Sozen Roshi went on to receive dharma transmission and inka shomei (aka, "clear evidence of the mark") from Sogaku Roshi, and in 1935 she opened Kannon-ji as a training center especially for women – both nuns and laywomen. However, men trained there as well, including Tangen Harada Roshi:

When Sozen Roshi established Kannon-ji, she said:

In the dokusan room, especially when working with students through the Mu koan, Sozen Roshi encouraged them with blows of the kyosaku (wake-up stick) and with bitter words like these:

"Don’t spout logic!"

"It’s just your ego!"

"That’s emotion!"

"That’s theory!"

"That’s interpretation!"

"What are you waiting for?"

"That’s a hallucination!"

"That’s just a belief!"

"That’s just an idea!"

"That’s just a blissful feeling!"

Kogen Osho notes that "Sozen Roshi was not just a formidable teacher; she also played a key role in the struggle for nuns to be given equal rights in the Soto school."

Indeed, Sozen Roshi worked together with Kendo Kojima Roshi and other women to challenge the Soto patriarchy. Kojima Kendo Daiosho's name is also intoned in many Soto centers' matriarchal lineage. In fact, Kojima Roshi was a student of Sozen Roshi and realized kensho under her guidance. Kojima Roshi's kensho story is included in the text, In This Body, In This Lifetime. Here is the culmination:

It is not a coincidence that two of the leading women who challenged sexism in Soto Zen – and attained their goals for full recognition of nuns – were enlivened women of awakening.

For more about Kojima Roshi, see:

Post-kensho training

Note that above, Kojima Roshi says that with kensho, she "[...] had broken through the first barrier." With so much emphasis In This Body, In This Lifetime on kensho, the first barrier, I want to highlight the following passage (selected from several that also emphasize post-kensho training) that makes it clear that kensho is just the beginning of the path of practicing awakening.

Sogen Saito Osho's entry concludes with this:

Shame as a source of great power

I recently saw this advice on Substack by a meditation instructor: "Let’s be gentle with ourselves in the process."

"Be gentle" is now the common understanding of how to work with our delusions – the heart of the self-soothing dharma narrative that traps would-be practitioners in the world of suffering. Indeed, many dharma teachers and practitioners today reject what they call the shame-based orientation of Buddhist cultures and replace it with the self-indulgence of the global secular culture, especially in the United States.

Does being gentle with our delusions of separation, merely practicing self-soothing dharma narratives, really lead to awakening? I see no evidence that it does. In my view, it merely fortifies the picking and choosing of the separate self. Freedom from birth and death cannot be found by adjusting conditions, because the addiction to trying to find freedom by adjusting conditions is itself to be stuck in the wheel of birth and death.

Another approach, that of the received tradition common throughout the Buddhist world, is to strongly and directly face and eliminate our personal failings and weaknesses that prevent us from following through on our vow to awaken for the benefit of all beings. Like Kojima Roshi said, “Hey, you can do it!”

In fact, "shame" is regarded as a wholesome emotional state in the Abhidharma literature, and is considered essential for the development of samadhi. Shame, in this sense, isn't wallowing in the feeling of being inherently defective – that's just self-indulgence in the delusion of an abiding self.

One of the most striking things about the women highlighted in the book, In This Body, In This Lifetime, is how they were not gentle with themselves or others. Truly, woman after woman through all of the 30 kensho stories, share their failings with an honesty that might be difficult to face. Because they were aware of the limited time available for breaking through, they worked with their attachments to their emotional states and their bodies in a rough, sometimes even brutal, manner.

Sozen Roshi and the zendo monitors used the kyosaku unsparingly, especially with those who were throwing themselves into the house of Buddha. For example, as one sesshin was just underway, Toshiko Nakamura had already received many blows of the kyosaku to her shoulder, and she noted in an understated manner,

"While taking a bath I looked and saw that my right shoulder was swollen. I was sad and irritated but thought to myself, 'After all, practice is not easy.'"

Late in the fourth day of sesshin, Etsujo Aoki chided herself:

What a coward I am. Why don’t I have the Bodhi mind to break through this shell? Weren’t Shakyamuni Buddha, Dogen Zenji, and all the older Dharma sisters able to cross this last line? It cannot be I am the only one who cannot! Mu-, Mu-, Mu-!

Etsujo then attained some stability with Mu, and still the monitors yelled at her, "You are unsteady!"

When Etsujo went to dokusan, Sozen Roshi pushed her:

“Just a little bit more. You must not sleep tonight. You will practice until the morning!”

Etsujo vowed to herself,

Even if it is my chronic disease of swollen tonsillitis coming back, I don’t care. Even if I were to vomit blood or break my throat open, Buddha is protecting me, I won’t die. And if I do, I will be satisfied. Where is there a more beautiful death than this? I came this far and I won’t retreat!

Others joined Etsujo in her all-night sitting in a nearby field. Etsujo writes,

"Before I knew it, I was unaware of sitting in the field and of the people behind me; I was just doing Mu. When I came back to myself, suddenly, I realized the absoluteness of Mu, everything was Mu. It is Mu. It is Mu. Isn’t it Mu?"

But in the morning, Etsujo repeatedly went to dokusan and Sozen Roshi repeatedly rejected her presentation, ringing her out, saying,

“What are you dawdling over?”

Sitting up all night, entering deep samadhi – dawdling? Yet, Etsujo pushed on and finally,

At 7 p.m., zazen started, and soon after that, the dokusan bell rang. How grateful I was! I jumped up and ran to the dokusan line. In the instant I grabbed the wooden hammer, I realized, Everything is Mu! I broke through. Both hitting the bell and standing up, it was all Mu. I went to dokusan. I was able to reply to all the successive questions of the Venerable Abbess without any hesitation, and I received confirmation.

In short, if your aspiration for this one precious life is just to feel good about yourself and be commonly unhappy, then shame is a hindrance. Go ahead and be gentle with your idea of your body and mind, filled as it is with delusions and limiting self-told stories. Take it easy on yourself. Be as comfortable as you can. And when you die, you will likely be very uncomfortable and fitfully wonder if you did what you could have with this life.

If you want to be uncommonly happy and joyfully realize the source of self-nature, shame can drive you to burn through it all. In this case, you will discover 31 true friends (including Sozen Roshi) In This Body, In This Lifetime, and you will find yourself brimming with a wholesome yearning for the timeless Way of awakening. And when you will die, you will likely be very uncomfortable and know that you did what you could with this one great life.

Thanks to Tetsugan Sensei for her many contributions to this post!

Coming soon for paid subscribers

"And All That We Had Gathered Fell Away:" Anne Hopkins Aitken's Kensho