Mountains are Not

Given our predilection to dig into the original sources to see what unexamined and/or forgotten treasures lie there, you might not be surprised that we did it again. You'll find the results below.

If you've been around Zen circles for more than a short time, you've probably heard it—at first, mountains are mountains, then after you practice for awhile, mountains are not mountains, and then finally, mountains are mountains.

A successor of the Sixth Ancestor (Dajian Huineng, 638-713, Great Mirror Insight Genius), Qingyuan Xingsi (660-740; Green Source Walking Contemplation), is credited with this early and simple stage system. Qingyuan's lineage successors, as you may know, include Dongshan, Dogen, and the present Soto lines.

Given our predilection here to dig into the original sources to see what unexamined and/or forgotten treasures lie there, you might not be surprised that we did it again. You'll find the results below.

Mountains and rivers

The following is our in-house translation of this important teaching. The underlined passages are highlighted in our comments below:

There are several gems here. First, it is notable that old master Qingyuan saw the circle of the Way unfolding in stages. Earlier in his life, as a promising young monk, Qingyuan was mired in conventional reality like all of us when we begin to practice the Way. He saw the scenery of life–mountains and rivers–as if they existed, so mountains and rivers were what they appeared to be.

There's also the implication here that at this stage Qingyuan's inner experience was "inner" and his experience of the outer world was "outer." That includes his karmic hindrances—the specific ways the grasping, aversion, lethargy, agitation, and skeptical doubt blocked his clarity. At this stage these hindrances are seen as "real" phenomena.

Now, there are those who count themselves among his successors who hold that the Buddha Way is just about noticing what's here now, allowing everything to be just as it is, without judgment or resistance. That is to settle with the first stage—mountains are mountains, and rivers are rivers—and live a life observing the scenery, blocked by hindrances, and forever estranged from the radical intimacy of the awake truth.

The second stage begins with Qingyuan intimately practicing with an awake teacher, i.e., the Sixth Ancestor. Under his guidance, Qingyuan discovered "...a singular point of entry." Then, the so-called scenery of his life–the mountains and rivers–were not mountains and rivers, and so there was no scenery. That also applies to the hindrances. At this stage, grasping, aversion, lethargy, agitation, and skeptical doubt are seen through as empty, nonlocatable, and neither arising nor passing away.

Late in this stage, Qingyuan famously reported to the Sixth Ancestor (given that mountains were not mountains), that he was not-doing even the four noble truths. In haggling with the Sixth Ancestor, Qingyuan joyfully exclaimed, "What stages can there be?”

The Sixth Ancestor confirmed his understanding, for the time being. For the full interaction, see Wansong's commentary to Record of Going Easy, Case 5: "Qingyuan’s Price of Rice":

Qingyuan, though, continued his practice, and reported that finally, after thirty-years of training, he'd found the "body at rest." In so doing, he discover that all along, mountains were mountains and rivers were rivers. Grasping, aversion, lethargy, agitation, and skeptical doubt, all along were exactly grasping, aversion, lethargy, agitation, and skeptical doubt. In this third stage, as Zen master Tenkei said, “Realizing is the same as not realizing.”

In the circle of the Way (a circle that unfolds in stages), Qingyuan did not skip from stage one to stage three without going through stage two (intimately realizing emptiness, verified by an awake teacher) and thirty-years of training, before finally coming to full stop—the body at rest.

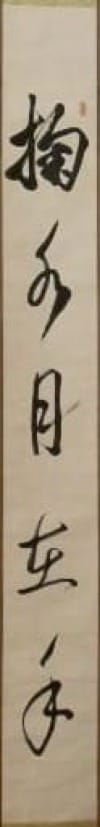

This incredible journey does not happen "naturally." We must thoroughly and intentionally steer our little boats. We must find a teacher. We must practice with uncommon diligence. We must scoop water from the stream with both hands in order to discover that the moon is fully illumined in our hands.

As I said above, Qingyuan's stages are often summarized, "...at first, mountains are mountains, then after you practice for awhile, mountains are not mountains, and then finally, mountains are mountains." In so doing, several crucial elements of the path are excluded: meeting an awake teacher, gaining entry (aka, kensho), and fully integrating this early intimation.

If you are a person who is swirling in the torrent of involuntary thoughts and who hasn't yet gained entry (Qingyuan's second of three stages), when you read or hear that you really and truly are already in the body of rest, and any aspiration to scoop water from the stream is unnecessary–spit out this pablum as rapidly as possible. Such unverifiable belief statements lack transformative power.

If you're new to the work, you might make a note of that.

This week at Shake Out Your Sleeves and Go

Bǎizhàng’s Wild Fox: "Does a Person of Great Diligent Practice Fall Under Karma?" Record of Going Easy, Case 8, in Brief

Next week at Vine of Obstacles Zen

"On Being Strict with the Self: Three Vignettes"