Is Just Sitting Facing a Wall Enough?

This way they’ll go on until the year of the ass....

The short answer is "no."

But this is a post with a big, bonus PDF attached, so let me tell you what that's about.

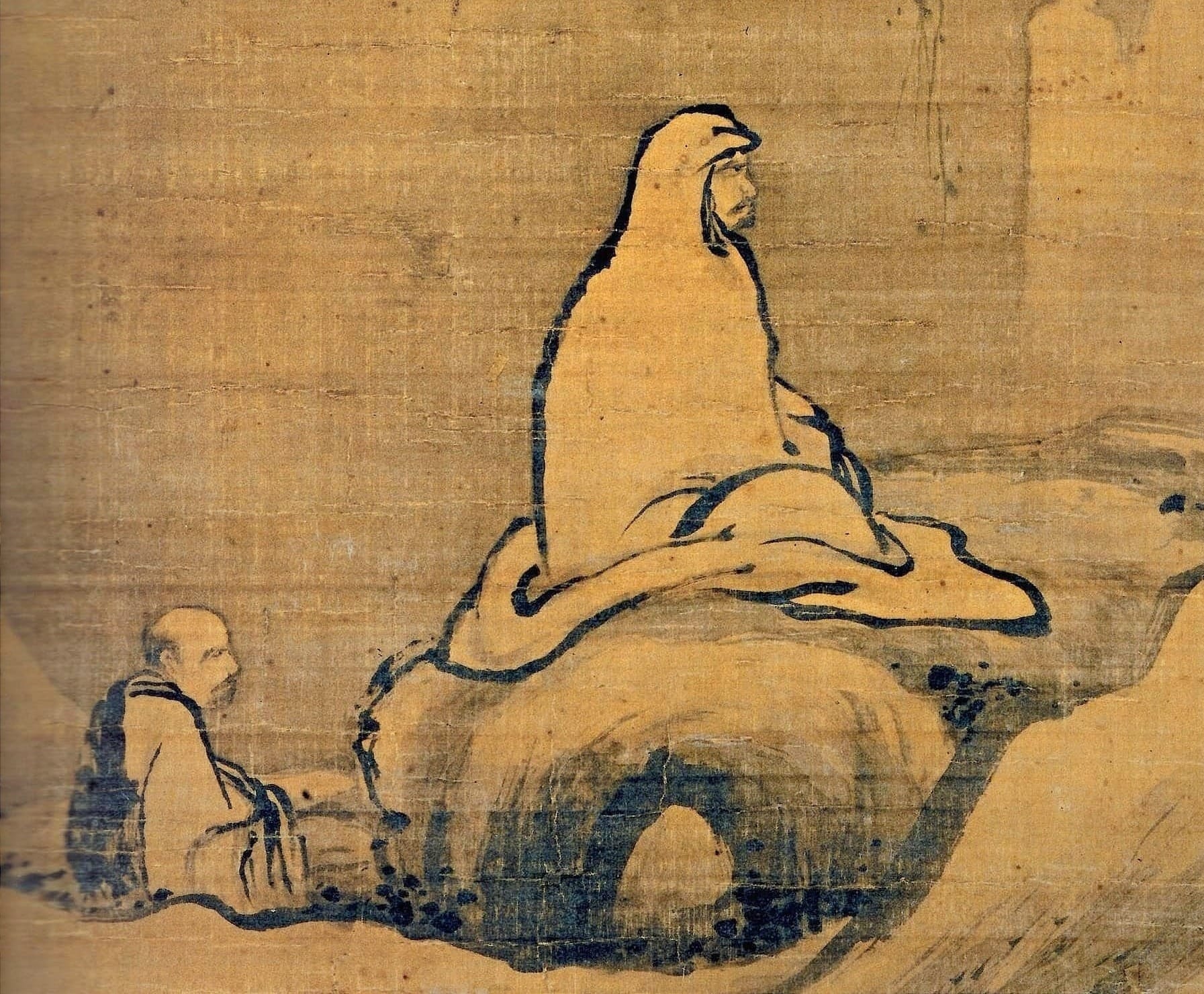

The first portion of the PDF has an original translation like those that I share with paid subscribers each month (thank you!) from The Record of Going Easy (Japanese, Shoyoroku). This month, it's "Luzu Sits Facing the Wall." As usual, the source for this koan commentary is the classic collection, The Record of Going Easy, that was pulled together with added verses by Hongzhi (1091-1157). The introduction, commentaries, and capping phrases (J. jakugo) were added by Wansong (1166–1246). I've indented and italicized the capping phrases throughout. And I've added footnotes to identify the prime suspects, as well as to explain various terms and phrases.

Here's the koan:

At first read, if you are aware that Soto zennist generally sit facing the wall and Rinzai zennists sit facing away from the wall, you might think this is a Soto vs. Rinzai thing. But it isn't. Both of the teachers in this case, Luzu and Nanquan, were ninth-generation successors in China through Mazu - the horse ancestor (that's the meaning of his name) who was two generations before Linji (Japanese, Rinzai).

Then what is the koan about? The question it addresses is this: is it effective to just turn and face the wall as a teaching device? Is turning and facing a wall enough to help wake people up?

Imagine contacting a Zen teacher to ask a heartfelt dharma question, like "What is the Way?" Or "How can I awaken?" And the teacher just turns and faces a wall. Wake up yet? Nanquan had his doubts too. And Wansong in his commentary (see the PDF) cites eight other great teachers for their opinions on this issue. Note: as a teaching device, it really isn't as clear-cut as I've made it sound.

In addition to a teacher making a dharma presentation by just sitting facing a wall, there's also an issue for the student: Is just sitting and facing a wall enough for you to awaken and undergo the post-awakening maturation process? In this sense of the question, sitting and facing a wall represents samadhi (aka, absorption). So the question is about whether absorption is enough to awaken without working with a teacher, without cultivating the subtle breath, without koan, without studying the buddhadharma, and without practicing the precepts with others.

A reader recently raised this same issue, asking in the context of the above koan, "How is Luzu's just turning to face the wall different from retreating into, or recoiling into, emptiness?"

Although I think that it's important to distinguish "real" emptiness from clinging to silence - pseudo-emptiness (the ghost cave of Zen) - just sitting can certainly be such a recoil. So I'm including in the second part of the PDF a selection from Yamada Koun Roshi's commentary (from the 1980's) on this case, "Luzu Sits Facing the Wall." The Yamada Roshi excerpt includes a passage from Yasutani Hakuun Roshi's commentary (from the 1960's) with a few of Yamada Roshi's comments inserted.

I found this to be a very good summary of their perspectives on samadhi, what I call the Post Meiji Soto Orthodoxy, as well as on MU and nonthinking. I would add this qualifier: in this excerpt Yasutani Roshi is very clear about the limitations of cultivating samadhi, but he does not emphasize the importance of samadhi for kensho. And after kensho, the practice of samadhi-prajna throughout the twenty-four hours becomes the focal point of post-kensho training. We call this the self-fulfilling samadhi (Japanese, jijuyu-zanmai).

By the way, I have edited Yamada Roshi's commentary a bit, mostly by re-paragraphing and exchanging the Japanese names for Chinese figures to Chinese names.

I would much appreciate hearing any comments you have about this passage.

All that said, here's the PDF:

Coming soon: "More on Facing a Wall" and "Simple Truths About Zen"