Dogen On Taking Refuge Through Life and Death

"Whether sleeping or waking, we should reflect on the virtues of the three treasures; whether sleeping or waking, we should recite the three treasures."

In the previous post in this death series, I raised these questions:

To explore these questions, I first looked at three critical passages from Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) and concluded that Dahui embraced the Mahayana's essential elements on dying and death, while he also added a couple twists. Specifically, but unsurprisingly, Dahui recommended his signature method – intimacy with a koan key-word through the dying and death process; and surprisingly, instead of vowing to be reborn in the Pure Land of a specific Buddha (the more standard Mahayana practice), Dahui vowed to be reborn in a Pure Land with all the Buddhas.

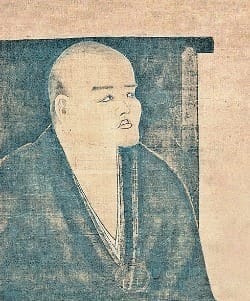

But underneath the above questions, I'm looking to offer you a range of death practices to consider for your dying process. Dahui's instruction (especially in the first two selections) are directed at those who have yet to have a definitive breakthrough, and are working with a teacher who has offered them the key word from a koan. In Dogen's (1200-1253) instructions that follow, he seems to be writing for those who have had at least a taste of awakening (aka, right view).

Here are the death posts so far:

Hongyi's Long, Last Moment

Why is the Long, Last Moment So Important?

How To Practice During the Long, Last Moment

Dahui On "Being Immediately Reborn in a Buddha Land"

In this post, I will examine four paragraphs from Dogen's "Mind of the Way" ("Doshin") – the Shobogenzo fascicle that includes Dogen's most developed instructions for dying and death. As with the post on Dahui's views, I will focus on identifying elements in Dogen's death instructions that present what I'm referring to as "the standard Mahayana approach," as well as elements Dogen adds that represent his contribution to practice during the dying and death processes.

I've also included several poetic interludes for those of you with a poetic inclination.

Mind of the Way

Dogen's dying and death section in "Mind of the Way" occurs after he recommends that we continuously devote ourselves to the three treasures:

Dogen then begins his discussion of dying and death while we are in-between one life and the next, i.e., in the bardo, or intermediate state, then he goes on with practices for entering our mother's womb, and while developing as a fetus, then he skips over a lifetime and lands just before death, and finally ends with practices for the moment of death.

I considered reorganizing these paragraphs so that they flowed from before death, to death, then to the bardo, and finally to fetal development and rebirth. However, I decided to give the old master some credit and stay with his disordered arrangement. After all, the discordant quality of the flow of this very life-death seems to be one of his essential points.

One further note before we dig further into "Mind of the Way:" Dahui is known today for his emphasis on the key-word method, a method he also recommended during dying and death. Dogen is known today by those inclined to the Post-Meiji Soto Orthodoxy for his shikantaza (just-sitting) method. However, there is scant evidence that Dogen actually taught or practiced shikantaza as a meditation method, apart from the phrase's koanic, key-word context – "just sit dropping body mind." Further, given that Dogen did not mention shikantaza in any of his several texts of zazen instructions, it is not surprising that he doesn't mention it here for dying and death either. His instruction is to just take refuge in the three treasures.

Interlude: Rujing's death poem

Sixty-seven years

Transgressions fill the heavens

I strike and suddenly leap

Living, I fall into the afterlife

What? Onto the next life

Death is irrelevant

Dogen on death practice in the bardo

For some context on the bardo, see:

In the above passage, Dogen summarizes the bardo teachings from Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakosha, or perhaps his comments simply align with the Abhidharmakosha due to his deep familiarity with the fundamentals of the Mahayana. In either case, the various temporary bodies one receives through iterations of the intermediate state is a standard pre-Mahayana and Mahayana teaching.

In addition, the Chinese Vinaya master Daoxuan (596–667) in his instructions for attending to the dying, directs the deathbed attendants to help the dying concentrate their thoughts on the three treasures. So in both the context and the content of the teaching, Dogen claps along with standard Mahayana approaches.

However, the degree to which Dogen focuses on this single practice – taking refuge in the three treasures – is indeed striking. This is a key point here, so I'll examine it in more detail below.

Dogen on death practice while entering our mother's womb

After discussing continually reciting the three treasures in-between lives, Dogen continues:

Notably, in addition to continuing to recite the three treasures, Dogen emphasizes that as we enter our future mother's womb, we should maintain right view. Maintaining right view is also an element that was stressed in other pre-Mahayana and Mahayana teaching as cited in the above post, "How to Practice During the Long, Last Moment."

But what is right view? Of course, it is the first step of the eightfold path, but what view is the right (i.e., round, complete, whole) view?

Generally, right view is defined as those views that align with the four truths (suffering, cause, cessation, and path). In addition, right view is defined as the view of an awakened one. In what follows, we'll find that Dogen strongly emphasizes the latter definition.

In "Mind of the Way," Dogen offers no definition of right view, but in "The Thirty-seven Factors of Awakening," he defines right view in the following remarkable passage:

Again, what is right view? Hiding the body inside the eye. Zen texts include frequent references to hiding the body. For example, in our Miscellaneous Koans, we have "Hide the body in a temple pillar." Carl Bielefeldt notes that other common examples are to "Hide the body in the Big Bipper," and "Hide the body in flames." But here it is "Hide the body inside the eye," meaning, inside awakening, inside an abrupt, nondual embodiment. The body becomes the eye itself, wide-open and awake with no shadow.

Dogen goes on to say that this hiding the body begins before there is a fully developed body and is the eye itself, the activity of awakening itself that develops into the body. This is certainly extraordinary karma. It is the koan realized (i.e., the genjokoan), the manifestation of the fundamental point. And the extraordinary Dogen sees this process of cultivating-verification unfolding within fetal development!

According to Bielefeldt, he once personally saw, is a reference to a saying by Dogen's teacher, Rujing (see his death poem above): "They once personally saw the Buddha; and so they don’t deceive." In other words, awaken once and then truly practice life after life. Yet, there are those who argue, despite a Sumeru-sized mountain of contrary passages like this one, that Dogen (and by insinuation, Rujing) were not into a personal, sudden awakening. Nonsense!

Dogen concludes his definition of right view in "The Thirty-seven Factors of Awakening" by stating that "...those who do not hide the body inside the eye are not Buddhas or Ancestors." Another striking statement!

In this short passage, Dogen has not only creatively redefined right view (strongly aligning with the view of awakening), but also redefined what it means to be a true Buddha or Ancestor – i.e., one who has the capacity to hide the body in the eye. Notably, he doesn't say that it is just anyone who has undertaken the appropriate ceremonies.

In addition, by adding right view into the process of being reborn, in "Mind of the Way," Dogen slides from what seemed like the process of an ordinary person in the bardo to the next-birth embodiment of an awakening being. But awakening is not a one-and-done phenomena, so Dogen exhorts the awakening being who is developing in the womb to continually make offerings, recite, and take refuge in the three treasures.

And remember, we're still in the womb making offerings, reciting and taking refuge. These could all be taken up as powerful koan:

"While you are in your mother's womb, show me how you made offerings to the three treasures!"

"While you are in your mother's womb, show me how you recite the three treasures!"

"While you are in your mother's womb, show me how you take refuge in the three treasures!"

Interlude: Dogen's death poem

Fifty-four years

Illuminating the highest heaven

I strike and suddenly leap

One touch shatters the thousand worlds

What? From head to foot, there is nothing to seek

Living, I leap into the afterlife

Dogen on death practice while dying

It is notable here that Dogen recommends a death practice with elements common across the tradition, and especially prevalent in the rinjū gyōgisho (death instruction) texts, including maintaining awareness and right view (as he refined it above) at the moment of death by means of a phrase, in his case, "I take refuge in Buddha."

Where the Pure Land folks would do Namu Amida Butsu, Dogen has the similar Namu kie Butsu. Dahui picked up a dried shit-stick. Whatever one picks up, the intent of the practice – harnessing the power of the last moment – is the same. That is, to burn through and transform harmful karma and be reborn in heaven, i.e., a god realm (Dogen is probably thinking of Tushita heaven where Maitreya Buddha waits to be born in the human world), or in a Buddha Land in order to train directly with a Buddha, and then take rebirth in the wandering-in-circles world to help living beings awaken.

The difference with the Pure Land instructions and the standard Mahayana approach is that Dogen, like Dahui, does not specify which Buddha Land to aspire to be reborn in (e.g., Amitabha's, Aksobhya's, Avalokiteshvara's, Shakyamuni's etc.). Nevertheless, like Dahui's Vow, Dogen's method of intoning Namu kie Butsu establishes a connection with an unspecified Buddha. In the same way, the Pure Land practice of Namu Amida Butsu establishes a connection with Amida Buddha. Namu kie Butsu and Namu Amida Butsu even sound a lot alike.

Dahui's view is much the same as Dogen's, although Dahui teases out the time with Buddha with "receive confirmation of complete enlightenment and merge with the reality-realm." I think it's fair to say that Dogen left those unstated but implied.

Dogen on death practice after death

So we're back to the provisional beginning. For Dogen, it seems, the circle of the Way begins in-between the traceless beginning and the traceless end. And by continually reciting the three treasures through the bardo, through the next life, through age after age, we may fully become a Buddha ourselves.

Dogen teaches that this process and practice – bardo, fetal development, rebirth, death, and the bardo (on and on), while ceaselessly taking refuge in the three treasures – is the Way of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. It is the embodiment of profound awakening.

Interlude: from Dogen's Bodhisattva Vow Poem

And it all arises from the broken heart of the Bodhisattva and the Great Vows, which Dogen simply expressed in this poem (thanks to Kokyo Osho for reminding me of this):

Awake or asleep

in a grass hut,

what I pray for is

to bring others across

before myself.

(trans., Tanahashi)

Wrap up

What was Dogen's perspective on dying and death? Did he see dying and death the same as other Mahayana masters or differently?

As with Dahui, Dogen clearly embraced the rebirth process commonly held by other Mahayana masters, including the bardo, and also stressed the power of the last moment, the importance of right view, and the power of a focused practice during the dying, death, and rebirth process.

In particular, Dogen's instructions are directed toward someone who has had a taste of awakening, such that they can develop their awakening through whatever temporary phenomena appear (bardo, entering the womb, fetal development, rebirth, and death), life after life, until they realize full Buddhahood.

However, the most distinctive feature of Dogen's instructions is his focus on the single practice of taking refuge in the three treasures.

Coming next in death

"Kokan Shiren On Contemplating the Emptiness of Dharmas While Dying"