Do Special Experiences Mean Anything?

We're in a strange moment in Zen in the West where, in at least nine of ten zendos, all "experiences" are lumped together and dismissed.

We're in a strange moment in Zen in the West where, in at least nine of ten zendos, all "experiences" are lumped together and dismissed.

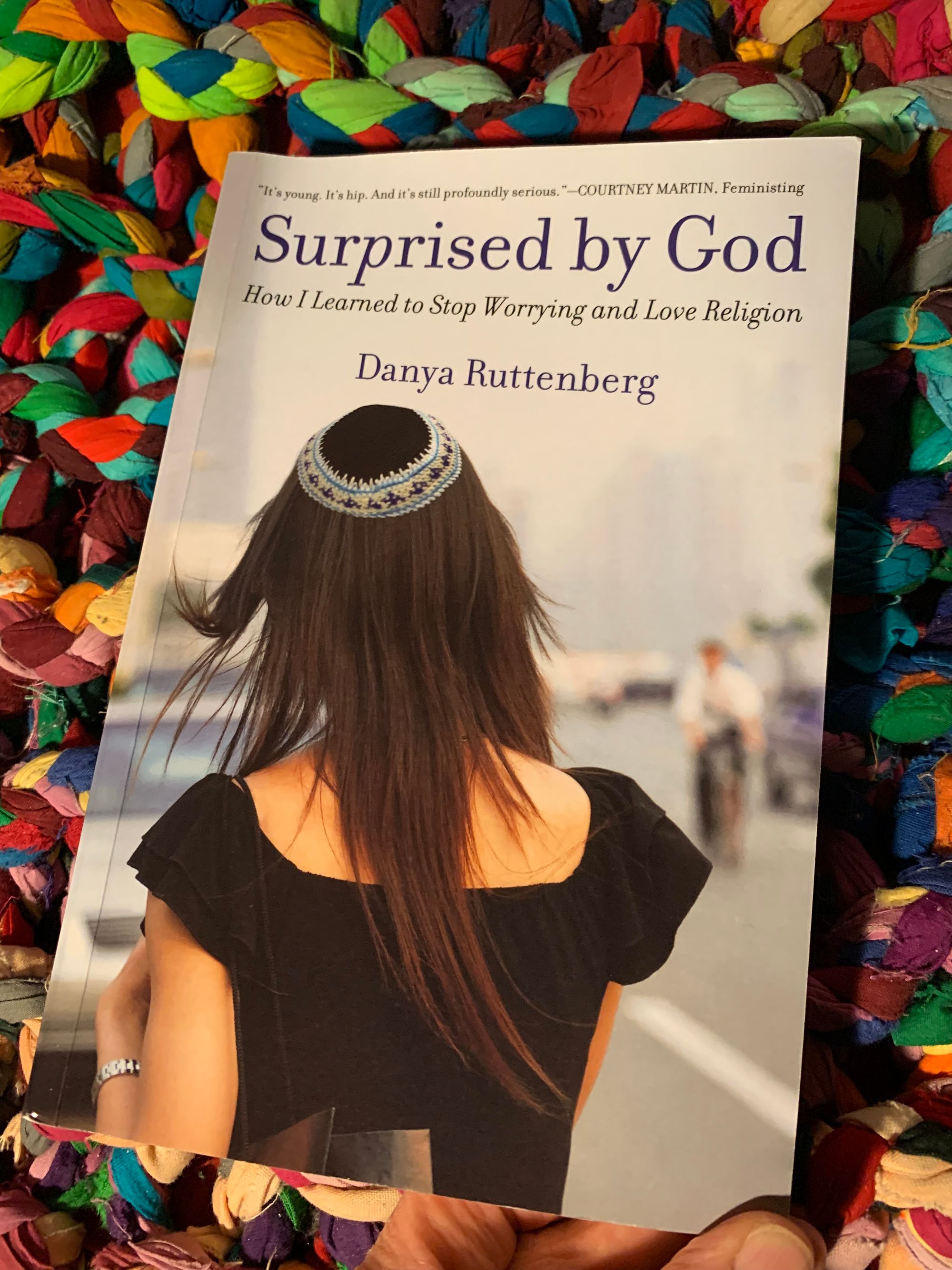

Take the one below, for example. Danya Ruttenberg, who was studying Judaism and also doing meditation practice with Zen teacher Norman Fischer, went to El Escorial, Spain, and after an arduous hike up the mountain, she sat down to rest. She tells us what happened next in Surprised by God (p. 120) - thanks to John Denko for pointing out this lovely book:

"I find it difficult to explain what happened next. I breathed deeper and deeper into the tree, and suddenly I could absolutely, completely see my consciousness in the tree, and then see the tree’s consciousness—whatever that means—somehow in my own mind and body. I looked at a bird. Just as I was the tree, I was the bird. There was only one consciousness, and it was mine and the tree’s and the bird’s and bigger than all of us and it was God’s. Everything really was nothing; I could see it. Just as the atoms in my legs were in motion and of fundamentally the same stuff as the ground, the ground was in motion and of the same stuff as the tree, and the same was true of the bird and the branch. It was creation and destruction, but it was really neither because it was all one thing, constantly changing form. Blessed are You, God, who resurrects the dead."

Granted, there are a lot of what we might technically identify as "woo-woo" elements in her experience (as there often are), due in part in her case to Ruttenberg's monotheistic orientation - but there are also wisdom elements. For those of us Zen teachers of the kensho persuasion, helping students cull out those wisdom elements from experiences like this and putting them to use in the nitty-gritty of daily life is the heart of the Zen work of the practice of awakening. We help students create meaning in the context of the Bodhisattva's wild ways of wisdom and compassion, embracing the dharma pilgrim in us all as we walk as if we were Sudhana in the Flower Ornament Sutra visiting fifty-three dharma teachers - monks, nuns, householders, tree spirits, you name it. Holy, holy, holy.

At the same time, empty, empty, empty. No holy, no meaning. Just don't know.

Ruttenberg shared the experience with her Soto Zen teacher, Norman Fischer. She tells it like this:

"During one of our meetings, I found myself telling him about my experience in El Escorial; I think that I was secretly hoping he would tell me that I had crossed over to some higher level of spiritual attainment. As I spoke, his face remained impassive. I finished, and there was a long pause. Finally, he said, slowly, 'You know that those experiences don’t mean anything, right? They might be pleasurable, and even compelling, but there’s no real meaning in them.'"

So "...those experiences don’t mean anything." On the one hand, I sing Yes! with Fischer. There is no experience that means anything of itself, even experiences like falling love or having a baby. All experiences are empty, empty, empty. No holy. We impute meaning to our experiences, including the meaning "those experiences don't mean anything," or, as one Zen priest is reputed to have said about an experience of his that he self-identified as a kensho, "it was as useless as a wet fart."

And, yet, Ruttenberg's book is largely an exercise in finding meaning within the context of a modern human who meditates and practices Judaism. Is that wrong practice?

We find a different perspective from Rinzai Zen teacher Jeff Shore: "There’s no need to deny any experience you have. On the contrary, fully experience it, and then you won’t get hung up in it. Odd as it sounds, it’s true: You can only be attached to something that you’re separate from — and longing for. No matter how sublime the state or experience, once self-attachment or self-indulgence arises, you’re stuck. A great danger that Buddhism continually warns us against. Go all the way through — experience it to the very bottom. Then you can’t help but let go — it dissolves of its own accord!" (1)

Yet what about meaning? What meaning might we impute to a meditation experience that would serve a person's heartfelt Bodhisattva vows to compassionately benefit beings in this swirling world? "A wet fart" just doesn't reach it. And yet not all experiences have a profound meaning. So discerning what is a step on the Bodhisattva path and what might be a distraction is vital to a life fully lived.

But back to "those" in "those experiences don't mean anything" for a moment - after all, "those" is a pretty vague category. Does it include just those experiences like this one with so many woo-woo elements? Or does it include experiences like Buddha's under the bodhi tree when he looked up and realized the Way? In other words, does "those" include "I together with the great earth and all beings attain the Way?" And everything in between?

If so, then isn't that the very definition of nihilism?

Often after a person has a dramatic shift in consciousness, either by finally shutting up for a short time or more importantly, through an abrupt taste of nondual embodiment, a wonderful, inconceivable joy arises. I've heard from people who have then gone to their Soto Zen teacher and been told to just let go of the experience.

The problem, when there is a problem, in addition to how the response can strike a student as dismissive, is that they cannot let go of it. Does it work to tell someone to just let go a falling in love? Or just let go of being seen through by the full moon on a summer night?

Just being told to let go without any skill instructions or dharma context is often unhelpful. If an experience has powerfully impacted consciousness, to be told just to let go can seem meaningless and utterly useless, yes, as a wet fart, even, which can stick around for sometime. These experiences when paired with proper skill instruction, can form the basis of a lifetime of living the bodhisattva dream. Or they can haunt a person as they get calcified in memory.

As it happens, Ruttenberg found Norman Fischer's response helpful:

"Though I didn’t understand it until later," she writes, "the fact that Norman didn’t validate me for this experience was tremendously instructive. I liked pretending that I was zealous, liked thinking of myself as something other than the true novice that I was. Norman’s refusal to mirror back to me my own illusions about my experiences and their meanings burst a balloon that I’d been carrying around inside—it hurt a little, but it ultimately created more room for me to see, potentially, what might really be" (pp. 153-154).

Quite meaningful, indeed. And granted, it is probably almost always good to have those identity-center balloons burst. But what then?

One of the great virtues of the system of koan introspection that has been passed down in various lineages from the great Hakuin Zenji is that it allows someone in a teacher-student relationship with someone skilled in that system, to do the culling out that I mentioned above. So, for example, if a student brought the above experience even to a hacker like me, especially if they were working with a first koan like mu, I would also not mirror back their illusions of grandeur, but simply start the checking questions. If Ruttenberg had flown through these thirty or so checking points - invitations to practice awakening right now - then we might say that she'd had a glimpse of the unborn and could offer her specific instructions for how to continue her practice.

I would also very likely share the person's joy - something that is very easy to do with someone who's just freshly opened their eyes to Buddha's world.

Ruttenberg writes that "The day after that, it was as though the El Escorial thing had never happened" (p. 121). So, more likely than not, she would have gotten stuck on the first question or two. The wisdom elements that sprouted through her experience might not have been clear enough for her to put them to use. In that case, the meaning of the experience could be in how it pointed to what is possible in the practice. An intimation of the truth, but not yet, not yet....

It might have given her great faith in the process. It could have led to great doubt - if everything seemed so perfect for those moments in El Escorial, where is that perfection now? And so it could have fueled her hair-on-fire introspection - what is this one great life?

The experience itself does not have those meanings. We find them in relationship.

(1) "Becoming One and Being Without Self: The Practice of Samadhi & Dhyana in Zen Buddhism" by Jeff Shore.